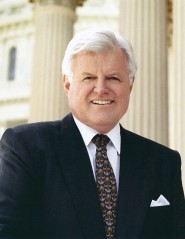

Does “the” mean “the,” or does “the” mean “a”?  That is the essence of the key question before the Supreme Court of the United States, which will hear oral arguments today in National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning. Ten years ago, when President George W. Bush was in office, the late Senator Ted Kennedy argued that “the” means the definite article. Today counsel for President Obama’s NLRB will say that it does not. As Senator Kennedy’s brief makes clear, this is not an inherently partisan question, and the meaning of “the” should not depend on which party controls the White House.

That is the essence of the key question before the Supreme Court of the United States, which will hear oral arguments today in National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning. Ten years ago, when President George W. Bush was in office, the late Senator Ted Kennedy argued that “the” means the definite article. Today counsel for President Obama’s NLRB will say that it does not. As Senator Kennedy’s brief makes clear, this is not an inherently partisan question, and the meaning of “the” should not depend on which party controls the White House.

At issue is the President’s authority to appoint government officials without the advice and consent of the Senate. As a default rule, the Constitution requires Senate approval for these appointments, but provides an exception: “The President shall have power to fill up vacancies that may happen during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session.” U.S. Const. art. II, S.2., cl. 3.

When can the President exercise this power? In other words, what is “the recess”? Can any break within a Senate session qualify, or does the phrase only apply to the recess that occurs between sessions?

In 2004, Senator Kennedy argued that President Bush’s appointment of a judge was invalid because it happened during a 10-day break after the Senate had reconvened in January 2004 for its second session. A break within a session does not create an opportunity to exploit the Recess Clause, Kennedy argued. “An intrasession adjournment is not ‘the Recess’ to which the Recess Clause refers.” (Kennedy Amicus Brief, p. 4).

The issue arose again after President Obama made appointments to the NLRB without the Senate’s consent. The Senate was not between sessions at the time, and was holding pro forma sessions of the sort that it used in 2007 for the express purpose of preventing President Bush from making any more recess appointments. President Bush appears to have agreed that these pro forma sessions had the effect of keeping the Senate in session and not in recess. At any rate, he made no further purported “recess” appointments.

The alleged “recess” that President Obama used in January 2012 – like President Bush in 2004 – was within a session of the Senate (an intrasession recess as opposed to an intersession recess). This was precisely the kind of appointment that Senator Kennedy’s brief denounced as unconstitutional.

Back in 2004 the Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit rejected Senator Kennedy’s argument and ruled in favor of President Bush. It held that the “Senate’s break fits the definition of ‘recess’ in use when the Constitution was ratified.” Evans v. Stephens, 387 F.3d 1220 (11th Cir. 2004). In contrast, the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit held that “the recess” does not mean just any break in proceedings, but rather is confined to the gap between sessions.

The lower courts are divided. Now it is up to the Supreme Court to decide which argument is correct: Senator Kennedy’s or President Obama’s.

Update: June 26, 2014: The Supreme Court of the United States held that the Senate is in session whenever it says that it is, so long as it has the capacity to transact Senate business.

Here’s a case where the intent of the framers makes sense to examine. Historically, it’s fair to assume that the framers intended that Congress would be a part-time body, meeting, doing its business, and leaving Philadelphia in brief sessions, so members could return home to attend to their farms or mercantile enterprises. The evidence for this is how they acted in the early years. The 6th Congress was adjourned from May to October, for example. But the framers had the forethought to anticipate that the government must have a some full-time leadership, in the name of the Executive Branch, and that the President would need to fill vacancies in his Cabinet. Of note is that Cabinet members and judges came and went with far more frequency in the 18th and 19th centuries than they do today. So it’s not a stretch to assume that two things were in play when the Constitution was written and in the early years of the Republic. In the years before air conditioning, Philadelphia was not a great place in the summer, and later, when the Capital was moved to Washington, the Senate regularly adjourned in May or June, in an effort to get out of the humid heat and feted swamp air.

So what is a recess. Is it the formal break after the Senate adjourns sine die, or a weekend off? I feel more comfortable with the first definition.

That said, the framers never anticipated the Senate would play games with its Article II, Section 2 “advice and consent” responsibilities.