Picture this: Corporation A enters into a contract with Corporation B, which hires Mr. Individual as an independent contractor. Perhaps in your mind’s eye you will imagine two links in a chain, representing a contract between Corporation A and Corporation B. But you will see no link between Corporation A and Mr. Individual because they do not have a contract with each other.

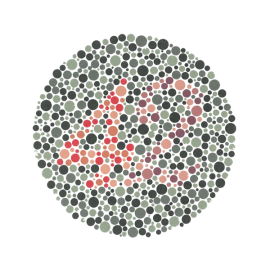

What if a court decides that Mr. Individual is not, in fact, an independent contractor but rather an employee of Corporation B and entitled to the protection of the Massachusetts Wage Act? Should Corporation A be liable to Mr. Individual, even though — unlike Corporation B — it had no relationship with him? “Yes,” said the Supreme Judicial Court in Depianti v. Jan-Pro Franchising International, SJC-11282, a case that brings to mind the Ishihara Color Test.

Some people will look at an Ishihara image consisting of colored dots and see a number. Others of us, myself included, will not. The Depianti decision demonstrates that I am not only color-blind; I am also contractual-duty-blind.

Jan-Pro is a Massachusetts cleaning company that operates a franchise system. It sells franchise rights to regional franchisees which, in turn, enter into contracts with unit franchisees. The unit franchisees are individuals who perform janitorial services.

One of Jan-Pro’s regional franchise holders was Bradley Mktg Enterprises, Inc., a corporation that sold a unit franchise to an individual named Giovani Depianti in 2003. Five years later, Mr. Depianti sued in federal court claiming that he was not really an independent contractor but rather an employee and, as such, entitled to the protection of the Massachusetts Wage Act, M.G.L. c. 149, Section 148B. Jan-Pro (yes, Jan-Pro) had misclassified him as an independent contractor, Mr. Depianti alleged.

Because it involved the interpretation of a state statute, the United States District Court asked the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to decide three questions, including “whether a defendant may be liable for employee misclassification… where there was no contract for service between the plaintiff and the defendant.” Answering in the affirmative, the Supreme Judicial Court held that Jan-Pro was the “agent” of the misclassification and merely used Bradley as its “proxy.” The lack of a contractual relationship between Jan-Pro and Mr. Depianti should not stand in the way of liability.

According to the Court, this was the will of the Legislature. The practice of employers wrongly classifying workers as independent contractors — and thereby avoiding the taxes associated with employees — was the mischief that the Legislature sought to remedy with the new Section 148B. Because the statute is a remedial one, said the Court, it is “entitled to liberal construction… with some imagination of the purposes which lie behind [it].” Depianti may suffer from a dearth of traditional contract law, but it has imagination by the bucketful, as the Court’s conclusion makes plain: “Limiting the statute’s applicability to circumstances where the parties have contracted with one another would undermine [its] purpose.” Any other conclusion would permit an “end run” around the Wage Act.

Certainly, when it enacted the independent-contractor provisions of the Wage Act, the Massachusetts Legislature may well have consciously intended to up-end the elemental principles that 1L law students learn in their first days of Contracts class. Absent a state equivalent of the Congressional Record, searching for evidence of such an intent would be in vain. The lone dissenter, Justice Cordy, stated: “I see no evidence of legislative intent… to change the body of law that governs the liability of such distinct entities.”

By expanding the reach of the statute so dramatically without positive evidence of legislative intent the SJC’s decision has made the law less certain and less predictable, and rendered Massachusetts that much more challenging to do business in. The statute already made it so difficult for arms-length parties of comparable bargaining strength to create an independent-contractor relationship that the employers’ group Associated Industries of Massachusetts claimed that “virtually no individual in Massachusetts can unambiguously pass the legal test.” Even some Democratic state legislators (including liberal-progressive types such as Representative Lori Ehrlich and Senator Stan Rosenberg) signed on to a bill that would loosen the law.

You do not have to be a freedom-of-contract fanatic hankering for a return to the Lochner era to think that Depianti v. Jan-Pro makes legislative action all the more urgent.